#21 Eulogy for John R. Tonneson

Transcript

When I first told my father I wanted to get my nose pierced, he sent me an email asking me to meet him in the living room on Tuesday at 4 pm.

Despite how it may sound, this was not a cold gesture coming from him; it was simply a matter of scheduling. You see, my father was a businessman of the purest sort: He was always on time, he put everything in writing, and he loved to get things done.

He took his job as a recruiter, landlord, and business-owner very seriously, and his job as my Dad even more seriously.

During the summers of my childhood, when I was out of school and had no responsibilities, I would receive a loud knock on my bedroom door every morning at 9 am sharp—not because I had somewhere to be, but because he felt that sleeping any later would be overindulgent.

When I was in elementary school, he forced me to sit down with him every Sunday for a procedure I absolutely dreaded. “Are you ready for corrected papers?” He’d bellow, then wait for me to drag myself out of my room and join him at the kitchen table, where we would go through all the worksheets, quizzes, and tests I had gotten back in my cubby that week and redo every single problem I had made a mistake on until I understood where I went wrong.

When I came home with my first Justin Timberlake CD, he snatched it out of my hands and returned it to me the next day with a sticky, which listed the songs I was and was not allowed to listen to, the threat of boom-box removal looming overhead should I ever dare to disobey.

By the time I reached middle school, I was a conservative, disciplined, overzealous nerd. I got straight A’s, was a faithful member of our town’s soccer team, and received very little attention from boys. All in all, an ideal situation for my Dad.

Then, I got to high school.

I started playing the piano. I saw a pair of unkempt, traveling spoken word poets perform at our school. It had not previously occurred to me that one could exist as an unkempt, traveling spoken word poet, but I found myself quite liking the idea.

I started writing my own poetry and performing it for my Dad. He listened, but I could tell, while he didn’t hate it, he didn’t quite like it, either. Mostly, he was just confused.

As I continued to dive deeper into music, poetry, and the like, I found myself becoming less and less interested in soccer. This was a painful evolution for my Dad to watch, because soccer was a huge part of our relationship. He attended all my games and took notes on how I could improve. If, at the next game, I showed enough improvement, he would reward me with a brand new CD. When it came to practice, not only did he drop me off; not only did he stay and watch; but he practiced, exercising on adjacent fields, my teammates squinting and pointing at the man running up and down the hills in the distance, whispering, “Steph… Is that your dad?”

My senior year, I revealed the news to him that I wanted to quit the team. My request to get a nose-ring followed shortly thereafter, and then, when I returned from my first year of college, I informed him, in his own matter-of-fact way, that I was switching my major from Business to English.

It was around this time that I saw my Dad starting to think: “Oh, shit.”

The conservative, mild-mannered, business-minded, practical, organized, stylistically understated, GPA-focused, retirement-saving, 5 year-planning, soccer-playing, 9-5 working daughter he had been trying to raise all this time, was turning out to be what, to him, may as well have been just about the scariest thing in the world: an artist.

But while he may have been nervous when he watched me swap out Intro to Marketing for a class on Bob Dylan, and while he may have felt fear when he watched me get into a serious relationship with someone who had a job-hopping history on LinkedIn, and while he may have been terrified when I started pointing to Lady Gaga as my biggest role model and inspiration, if there is one thing that never changes about John Tonneson, no matter the circumstance, it is this:

John Tonneson shows up.

He showed up to every talent show.

He showed up to every musical.

He showed up to every open mic night, restaurant gig, contest, concert, spelling bee, and poetry reading, even if he had to travel across state lines to get there.

He proudly moved his post from the bleachers to the stands. He took notes on my songs instead of on my games. For Christmas, he gave me a new guitar instead of a new pair of cleats.

And then, I got to watch him.

I watched him pick up that same guitar he gifted me and rekindle his long-lost passion for the instrument.

I watched him give Lady Gaga a chance, and, in his musically intelligent and unemotional way, identify Artpop, her most abrasive album, as a masterpiece that he listened to on the reg.

When I started podcasting, I watched him create a Spotify and sit through every episode of my show. Eventually, he started listening to other shows, too, and, like me, became a podcast fanatic. Then, I watched in shock as my father, the most utilitarian man I’ve ever met, started texting me links to interviews with spiritual teachers like Deepak Chopra, whom he, never stepping too far out of character, referred to as “a fruitcake who had a lot of good advice.”

Through his entire cancer journey, my Dad behaved no differently than he always had.

When he was first diagnosed, he researched, consulting doctors all over the country.

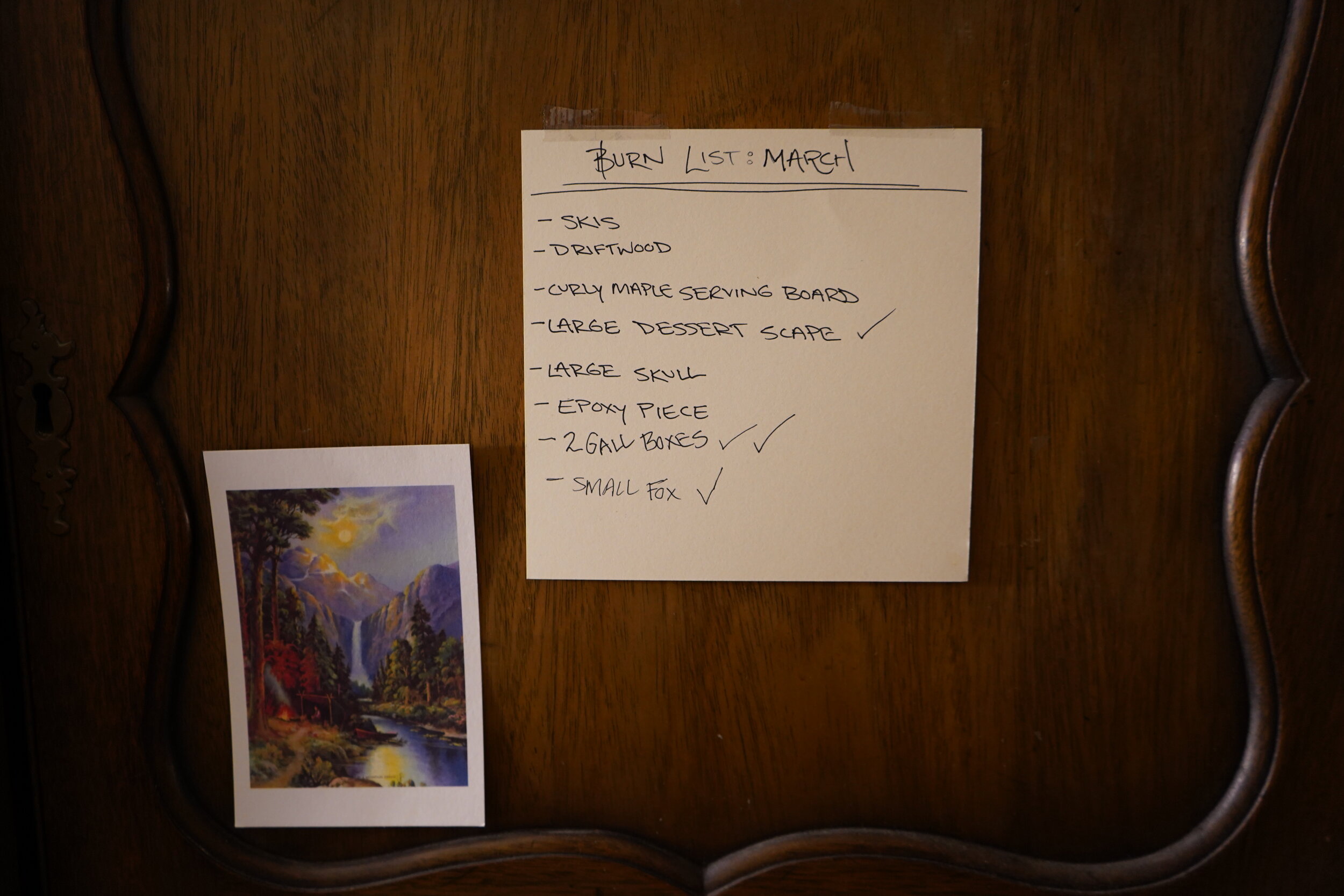

When he learned the treatments weren’t working, he prepared, fixing everything he could think of at his rental properties so they’d be left in perfect condition; sorting through his filing cabinets so all logistical matters would be straightforward; and even planning this funeral, down to every last picture, so he could be remembered exactly how he wanted.

And finally, when his liberal, bold-mannered, quasi-business-minded, semi-practical, disorganized, stylistically overstated, non-GPA-focused, non-retirement-saving, 6 month-planning, piano-playing, freelancing daughter, requested to make a podcast episode with him—not necessarily to share, but at the very least, to treasure forever privately—John Tonneson, once again, showed up.

Even though he agreed to my request without hesitation, I must say, there are few things in my life that have terrified me more than interviewing my Dad on his deathbed.

My intention, I knew, was to create a beautiful portrait of him and capture even the smallest glimpse of the magnificent man he was. The thought of even slightly perturbing either him or Nancy, however, which I realized I may have already done by even suggesting the idea, during what was already such a difficult time, was paralyzing.

Still, I pushed myself to give it a shot. I believed in the spirit of what I was doing, and if I could just do it the right way, then maybe, just maybe, that spirit would shine through.

We did the interview.

I made a rough cut.

A few days later, the three of us sat down and watched it together.

I held my breath for the full hour, too scared to check their facial expressions, wondering the whole time whether they were enjoying it or crawling out of their skin.

When it was done, I ripped off the bandaid and looked at them. Both of them were smiling. Not only were they in mutual agreement about loving the episode, but they were also in mutual agreement about wanting it to be shared.

The next morning, my Dad asked me when it would be published.

“I’m not sure,” I said. “Why? You want me to publish it… While you’re still around?”

He grinned and nodded. “I want to see what people say. And, I really appreciate you doing it, because I think it captured some of the best moments of my life.”

This—my Dad telling me on his deathbed that our podcast episode captured some of the best moments of his life—was the best moment of my life.

Sadly, he passed before I could publish the episode. He did get to watch the final cut with his friends, Chuck and Martha, though, and knowing my Dad, sharing it with a couple people that mattered to him was likely more than enough.

As I reflect back on our relationship; our similarities and our differences; and all the times we struggled to understand each other, what I realize my father taught me about love is that is love not about understanding.

He taught me that love is about showing up, even, and especially, when you do not understand.

When you don’t understand why the person you love wants to get their nose pierced, you grant them permission to do it anyway, even though it will hurt you deeply.

When you don’t understand why the person you love does not want you to get your nose pierced, you don’t go through with it—even after you’ve fought for and gained their permission—because you know it will hurt them deeply.

Love is showing up to poetry night when you don’t understand poetry.

Love is showing up to soccer practice after you said you were quitting the team.

Love is my stepmom, Nancy, showing up, day in and day out, when her partner became terminally ill, cooking his meals, organizing his pills, and kissing him on the forehead every day until the day he died.

Love is our neighbor, Rick, showing up to our house in the middle of the night to offer comfort and medical advice as one of them was about to pass.

Love is Nancy’s daughter, Natalie, flying home from a business trip and being away from her child, and Jen bringing her child, so that they could show up on their mother’s doorstep in the aftermath of a tragedy, and ask, “How can I help?”

Love is Lucia, my childhood best friend, booking a red-eye in the middle of her vacation and flying across the country, all without being asked, so that she could show up to the funeral for my favorite person in the world.

Love happens when you do not understand. You do not understand your loved one, you do not understand God, and you do not understand life, but still, somehow, you show up. You show up with the faith and the hope that one day, you will understand. You will understand the poem. You will understand the illness. You will understand your father, your daughter, the 9 am wakeup call, the math problem, the nose ring, the diagnosis, the death, and the life.

And when you show up for long enough, with enough faith and enough hope, that one day, you will understand, often times, you do.

But even if you don’t, it doesn’t matter. Because at the very least, you showed up.

#20 Dad, Hospice Patient: “I’m at peace.”

John Tonneson (my Dad) knew he was going to die. Still, he was at peace.

John Tonneson (my Dad) knew he was going to die. Still, he was at peace.

#18 Cross-country Movers: “These questions don’t go away.”

What is it like for people twenty years apart to be grappling with the same life questions?

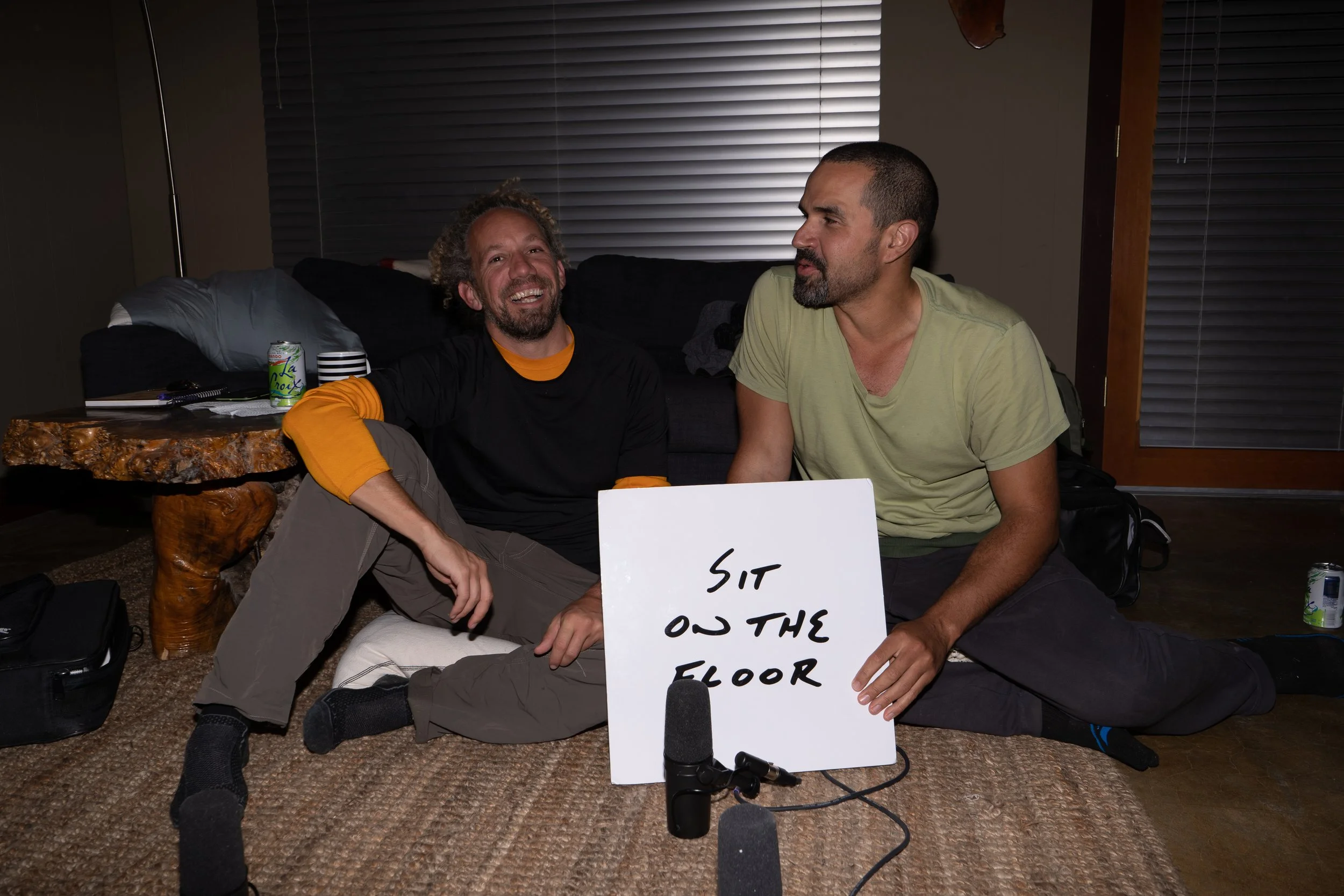

When we sat on the floor of Karim’s airbnb in Joshua Tree, CA, he and his friend, Jonah, told us.

#17 Immigrant: “Don’t forget where you come from.”

What is it like to immigrate from Mexico, raise ten kids, and become an 82 year-old shopkeeper?

When we sat on the floor of his roadside antique store in Santa Anna, TX, Francisco told us.

#16 Cardiologist: “It’s a calling.”

What’s it like to have people’s lives in your hands every day—literally?

When we sat on the floor of our airbnb in New Orleans, LA (at 3:20 am), Singh told us.

#15 Home-Sharer: “I’ve never met a stranger.”

What is it like to open your home up to everyone you meet?

When we sat on the floor of her house, The Bywater Wonderland, in New Orleans, LA, Stacy Hoover told us.

#13 Influencer: “I still struggle with wanting to be smaller.”

What is it like to be celebrated for your appearance and still wish you looked different?

On the floor of her house in Atlanta, GA, Claire DiMeglio told us.

#12 Dive Bar Regulars: “Without love, you can’t live.”

What is it like to turn strangers into chosen family?

When we sat on the floor of Steady Eddy's Pumphouse in Matthews, NC, Travis, Stick, and Sarah told us.

#11 Wall Street Investor: “A corporate job is like a drug.”

What is it like to hate your prestigious, high-paying job?

When we sat on the floor of the office space in his apartment complex on Wall Street, [Anonymous] told us.

#10 Ex-Mormon: “Keep questioning.”

What’s it like to question a belief you were raised on?

What’s it like to question a belief you were raised on?

When we sat on the floor of her apartment in New York City, Jenny, former member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, told us.

#09 Chef: “We’re still here.”

What’s it like to give everything to your dream?

When we sat on the floor of her restaurant, Moonshine 152, in Boston, MA, Asia Mei told us.

#08 Restaurant Owner: “The miracle will come.”

What’s it like to realize what’s most important to you after losing your life’s work?

When we sat on the floor of her restaurant, La Bodega, in Watertown, MA, Analia Verolo told us.

#07 Cross-Country Walker: “Your native environment is your authentic life.”

What’s it like to walk across America, write a book about it, and then discover the more deeper, psychological reasons why you went in the first place?

When we sat on the floor of his friend’s barn in Freeport, ME, Andrew Forsthoefel, author of “Walking to Listen,” told us.

#05 Language Professor: “I’m interested in people, period.”

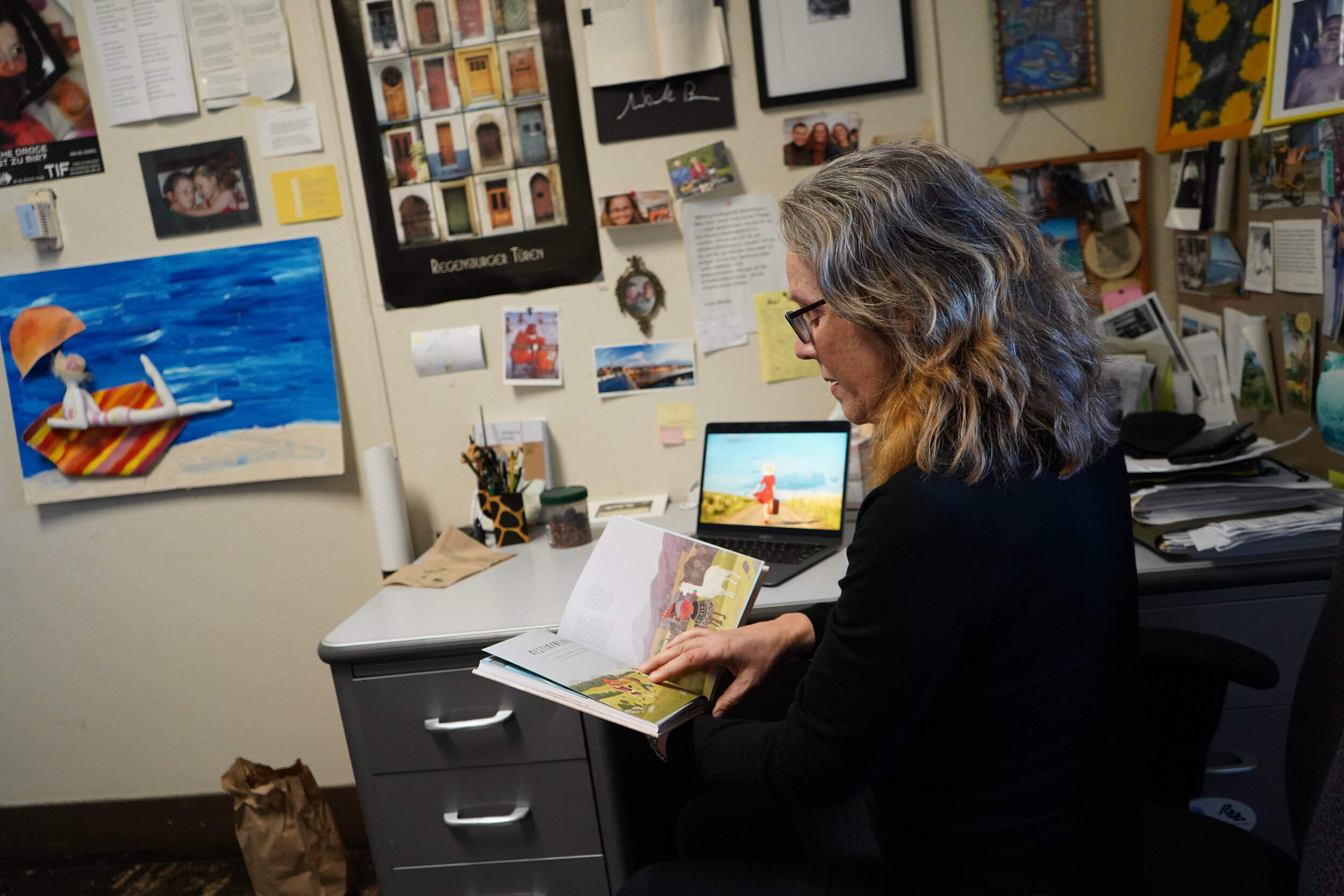

Adriana Borra grew up in three European countries. Then she moved to the United States.

Photos taken in her office in Burlington, VT.

#04 Artist + Performer: “The real work doesn’t have an audience.”

Princess Nostalgia used to share her innermost thoughts on social media. Then she deleted it.

Photos taken in her apartment in Burlington, VT.

#03 Recent Grad: “I want to be average.”

Margit Burgess was at the top of her class. Then she realized she didn’t want to be.

Photo taken in my apartment in Somerville, MA.

#01 Touring Musician: “I was pretty committed to sacrificing anything.”

Devin Mauch is the former drummer of The Ballroom Thieves and the founder of The Wild Electric.

Photos taken in his home in Portland, ME.